The grain of the material in design

Technology as the modern designer’s material

The modern designer’s primary material is technology. To effectively design and make digital things, we need to deeply understand our chosen technology’s embodied affordances, characteristics, and limits – i.e. the grain of the material. This is true whether you are designing an espresso machine, an app, a chatbot, or a car.

Immerse yourself in serious play with technology, and you’ll become a better designer, able to invent new design approaches through your tacit understanding of the material.

The grain of the material

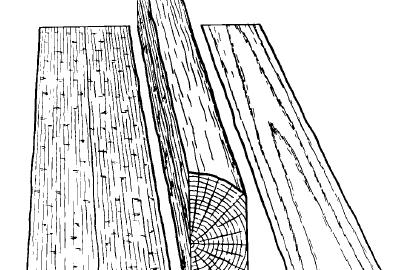

If we think of technology as a material for design, we can make analogies to traditional material craft. For example, in working with stone and wood, the craftsperson has to know the characteristics of the materials they are working with. In the case of grain, which is embedded in the work piece as a result of how the wood grew or the stone was formed, it affects how hard it is to cut, where and how it will break, what it looks like when cut at different angles, and so on.

About Carving a Stone - To carve a stone, you must first consider and examine the block you intend to work with. Is it soft or hard, brittle or crumbly? Are there cracks? Is the grain weak or strong? If the stone is particolored, where might the effect be strongest? After some exploration, I prefer to make a plasticine maquette, or model, of what I intend to carve. Many sculptors skip this stage, but I find my eyes and fingers wiser than my mind and the stone. by Scott Owens

Because of the particular characteristics of a specific workpiece’s grain, a design can’t simply be imposed on the material. You can “go with the grain” or “go against the grain,” but either way you have to understand and feel the grain of the material to successfully design and produce a work. In other words, there is an intimate, almost visceral relationship between the material and the design, and the outcome is a result of integrating the design into the grain.

The “grain” of the material is a metaphor for all the potentials and limits of whatever material you are working with - electronics, AI, wood, or mix of materials you’ve chosen. It be might how the affordances and limits of a touch-screen affect navigation, the way the dataset an AI model is trained with influence its biases, or how the sensitivity of a proximity sensor affects the timing of a door opening. Designing technological artefacts can’t be done without considering the material.

Design is an intimate and tactile collaboration with the technology.

This is why modern designers must directly engage with technology, learning some code and electronics, digging in as skilled craftspeople. The next time you design something, understand and embrace the grain of the project’s particular technologies. Find how you can work with or against them to best integrate the tech in the expression. Train your eyes and fingers to know the material.

Note: Bruce Sterling first introduced this idea to me in 2005 when we taught a class called The New Ecology of Things at Art Center College of Design. At the time, he was about to publish his book Shaping Things where he mentions this aspect of design. The concept is also discussed in the context of thinking through making by Donald Schön in his landmark 1984 book The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think In Action. See also the paper On Technology as Material in Design by Johan Redström.

I have found with digital natives, they don't think to "open the hood" and understand how the technology choices (often outside their control) impacts their design.